by Clayton Small, PhD

“Why are you still holding on to the past? It’s been long time ago!” Most American Indian–Alaska Native (AI/AN) people have heard this comment from a non-Indian at some time in their lives. Upon hearing this comment, they shake their heads and say to themselves, “Where do I begin, and how do I help you understand?!” This cultural divide is very real and is caused by misunderstanding, lack of knowledge, denial, and unwillingness to hear the truth.

Humans are for the most part capable of forgetting and forgiving after a traumatic experience when and if that experience stops, but unfortunately, many AI/AN people continue to experience colonization (although colonization takes different forms today), racism, and stereotyping. Despite the efforts of some healing movements in Indian country, the devastation of losing their land, the imposed laws that violated their culture, and the broken promises by the government continue to affect the daily lives of Native people and persist in creating a feeling of mistrust, betrayal, and doubt.

Humans are for the most part capable of forgetting and forgiving after a traumatic experience when and if that experience stops, but unfortunately, many AI/AN people continue to experience colonization (although colonization takes different forms today), racism, and stereotyping. Despite the efforts of some healing movements in Indian country, the devastation of losing their land, the imposed laws that violated their culture, and the broken promises by the government continue to affect the daily lives of Native people and persist in creating a feeling of mistrust, betrayal, and doubt.

Most Americans are oblivious to the truthful history of what the AI/AN people experienced. What happened to Native people was inevitable in terms of the federal government wanting the land and gold in the homelands of AI/AN people. How they took these resources is unconscionable when viewed in the light of truth. These acts include the Indian problem being given to the Department of War, after which entire tribes were killed, forced from reservations, and forbidden to practice their spirituality-religion; buffalo and horses were killed and diseases introduced; children were sent to federal government or parochial boarding schools; and families were relocated to cities. The policy at the boarding schools was “Kill the Indian and save the person.” So again, “Get over it and move on!”

AI/AN people struggle with healing challenges that run deep and result in unhealthy behaviors that are passed on to the next generation. Ongoing traumatic incidents for AI/AN people result in unhealthy ways of coping that lead to tremendous health disparities for many Natives compared with other races in the United States. It is common knowledge that the causes of these disparities for AI/AN men, for example, are rooted in historical trauma, racism, impact of colonization, loss of traditional roles, loss of connections to cultural ceremonies and spirituality, poverty, and unemployment.

Increased Risk for Suicide

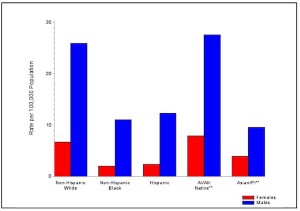

AI/AN death rates are nearly 50% greater than those of non-Hispanic whites (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2014). For AI/AN youth, suicide fatalities and related risk factors––including substance abuse, violence and bullying, coping with trauma, and depression––have reached a crisis point. According to CDC, suicide rates were nearly 50% higher for AI/AN people compared with non-Hispanic whites, and they were more frequent among AI/AN males and persons younger than age 25. CDC concluded that patterns of mortality are strongly influenced by the high incidence of diabetes, smoking prevalence, problem drinking, and health-harming social determinants.

In May 2013, the Men’s Health Network in cooperation with the Office of Minority Health and Indian Health Services developed a report to raise awareness of the growing health disparities among AI/AN males in the United States, entitled “A Vision for Wellness and Health Equity for American Indian and Alaska Native Boys and Men” (Men’s Health Network, 2013). The report suggests that health disparities among AI/AN men compared with women and all other U.S. racial and ethnic groups are extreme and the situation is worsening.

For example, the CDC reports that more than half of American men’s premature deaths are preventable and, even excluding pregnancy-related office visits, American women make twice as many preventive care visits as men. AI/AN males experience death rates 2 to 5 times greater than AI/AN females for suicide, HIV/AIDS, homicide, unintentional injuries, diabetes, firearm injury, and alcohol-related deaths. For cancer, heart disease, and liver disease, AI/AN males experience death rates 10%–50% higher than AI/AN females (CDC, 2014).

Barnes, Adams, and Powell-Griner (2010) documented that, overall, AI/AN males experience greater disparities in health status and general well-being than any other group defined by the combination of race and gender. In their survey, AI/AN males indicated often feeling “hopeless” and “worthless,” thus highlighting the tragic and disturbing state of all disparities, including the extremely high rates of suicide among AI/AN males for the age groups ranging from adolescents to mid-life.

These contributing social factors in Indian Country are a call to action by tribal leaders and federal agencies to take a more assertive approach in public health prevention, intervention, and treatment of these escalating health disparities among Native populations in the United States. Unfortunately, very little research to date has been funded to Native organizations to study the root causes and develop AI/AN men’s prevention and intervention culture- and strengths-based curricula.

Finding common ground between AI/AN and non-Indians (including federal, state, and city agencies) requires, first, an awareness of the concept of colonization (Blauner, 1972) and realizing the devastating effect that it creates, especially if the colonists continue to practice its power over the colonized. Second,the truthful description in history books as to what really happened historically to AI/AN people needs to be told. In addition, it is important for AI/AN people to understand the impact of colonization, to acknowledge it, and to overcome the challenges for the self, family, and community. This healing process for AI/AN people requires partnerships with federal and state agencies that have a common understanding of the historical context and a consensus among stakeholders about how to proceed.

More research and approaches are needed for AI/AN men that will validate the causes of the health disparities and lead to appropriate interventions. President Obama’s White House initiative, “My Brother’s Keeper” (http://www.whitehouse.gov/my-brothers-keeper), has potential to meet these needs for AI/AN men. A beginning would be the funding of a National AI/AN men’s Resource and Training Center that could provide awareness, technical assistance, and training for AI/AN males throughout Indian Country, as well as assist in the development and implementation of programs for AI/AN men at the reservation and urban community level.

In an effort to address some of the problems facing AI/AN people, Native PRIDE, a national AI/AN nonprofit organization based in New Mexico (www.nativeprideus.org), has developed two curricula: Native HOPE (Helping Our People Endure) and the “Good Road of Life: Responsible Fatherhood” programs.

Native HOPE

Native HOPE is a suicide prevention, peer-counseling curriculum (youth helping youth). This program addresses suicide prevention, violence prevention, stress and trauma, and depression. Clayton Small, PhD (Northern Cheyenne), created this curriculum in 2004 because he realized that most suicide prevention programs simply provided education and awareness and did not incorporate culture- and strength-based approaches or integrate healing into the process. Because of the historical context already examined, Native PRIDE recognized that these enhancements were critical to the Native HOPE curriculum. In addition, the interactive, Native HOPE curriculum allows AI/AN people to address serious health and wellness challenges while having fun learning.

The curriculum is delivered to approximately 2,000 youth per year in school and community settings throughout Indian Country. It consists of a 1-day training of trainers of local teachers, counselors, mental health professionals, substance abuse counselors, social workers, spiritual and traditional healers, and so on. They practice being a clan leader and assist Dr. Small in conducting a 3-day training with youth. This team walks through the program, practices skills in group process and facilitation, and is present during the 3 days. This builds capacity of this team to replicate the training in the future with other youth from their school and community. The process moves fluidly from the large group to small clan groups. The adult-youth ratio is one adult to from six to eight youth in the clan groups. The youth know immediately that this is a cultural gathering because of the use of prayer, humor, songs, dances, artwork, and medicines such as cedar, sage, and sweet grass. The youth and adults are challenged to share their tribal-specific culture during the 3-day retreat, and evening activities are encouraged, such as talking circles (support groups), sweat lodge, and social dances. A Spirit Room is created where youth can have one-to-one conversations with counselors anytime during the 3 days. The adult team conducts a debriefing session at the end of each day to review progress and identify at-risk behavior that needs immediate follow-up, for example, suicide, violence, or abuse and neglect. Great care is taken to create a safe environment for the youth, and they quickly feel comfortable in an atmosphere where a sense of belonging is maintained.

During the program, youth share openly and honestly about their life, family, and community in the clan groups and large group activities. Tears of healing are often demonstrated by youth, as well as fun and humor in the team trust-building activities. The youth often share, “This program saved my life” or “I know how to help my peers” and “It’s okay to ask for help.” The 3rd day includes the youth developing a strategic action plan for follow-up activities. This includes organizing a youth council that conducts ongoing prevention and leadership activities; conducting fundraising and sponsoring talking circles (support groups); conducting presentations to the school board, tribal council, and parent groups; and conducting peer-to-peer messages (role playing). This process is effective and validates that working with AI/AN youth requires a comprehensive cultural approach that incorporates wellness and healing.

The Native HOPE curriculum is endorsed by the Indian Health Services and SAMHSA as an effective culture-based prevention program. We are thankful that the federal agencies are embracing culture-based programs, even though they have not all completed the vigorous, time- consuming, and costly evidence-based protocol for effectiveness. We know this process works because we hear it directly from the AI/AN youth, and the evaluation data show evidence that culture-based programs make a positive impact on the well-being of AI/AN youth.

Good Road of Life: Responsible Fatherhood

The “Good Road of Life: Responsible Fatherhood” is a culture-based curriculum that uses sources of strength such as spirituality, humor, and healing to assist Native men and their family members to address the impact of colonization, trauma, racism, and other challenges that threaten the well-being of children and families. The program was funded by the Administration for Native Americans (ANA) to develop, field-test, and make available their culture- and strengths-based curriculum to AI/AN men, women, and families for 4 years (2008–2012).

The “Good Road of Life: Responsible Fatherhood” program is based upon the doctoral dissertation study of Clayton Small (Northern Cheyenne) and was completed in 1996 at Gonzaga University (Spokane, Washington). It addresses challenges in wellness and recovery for AI/AN men. This ANA project was implemented by Native PRIDE, who delivered 10 trainings in five tribal communities, reaching 895 Native men, women, and family members. Pre- and posttests of AI/AN male participants indicated enlightened self-awareness of the relationships with their own fathers and families and learning “letting go” (healing), communication skills, and forgiveness. The Administration for Native Americans (ANA) currently funds “Responsible Fatherhood” programs to AI/AN tribes and organizations, yet it is not enough to meet the tremendous need to intervene with AI/AN men to help address their personal wellness challenges that, if addressed, will lead to the elimination of domestic violence and incarceration of AI/AN males and promote increased quality family time and family preservation.

Men with depression and suicide issues, substance abuse, or domestic violence issues were referred for support and counseling. Participants made commitments to complete follow-up homework, such as joining talking circles (support groups), exploring spirituality and sources of strength, researching family history (behaviors), forgiving parents, and increasing quality family time. The participants worked in a peer-counseling (adults helping adults) approach with at least one other adult from their community. Several tribal colleges, substance abuse programs, social services programs, and mental health programs are integrating the GRL into their work with clients. As a result of this project, Native families have more involved spouses, fathers, sons, and brothers who can draw upon sources of cultural strength, as well as benefit from other men who are a positive role model for their communities.

Next Steps

The Native HOPE and the Good Road of Life are two examples of culture- and strengths-based approaches that are effective prevention and intervention programs for Native men, women, youth, and families. What makes these curriculums unique is their focus on strengths, culture, humor, spirituality, and participation. We create a safe environment (belonging) for participants and utilize Native stories, art, and songs to introduce themes (risk factors) that need to be addressed by participants. Humor and fun are an important element for Native people. It is essential for prevention trainings to incorporate interactive humor as a means to create a safe place for learning, address serious risk factors, and promote healing in the context of utilizing culture and spirituality. Federal agencies are beginning to acknowledge this learning process for Native populations and endorse culture-based approaches more so than in the past.

More funding is needed for Native communities to utilize these culture-based approaches as most do not have the resources to pay for the services on a fee-for-service basis. Reducing the health disparities among Native populations is not a quick fix due to the historical trauma, racism, poverty, and other ongoing daily challenges of survival for Native people. Healing can help move individuals from surviving to living a full and joyous life. This renaissance movement is catching fire in Indian Country, and it is exciting and impossible to resist. It is a demonstration of the resiliency of Native people of North America who overcame a federal policy of colonization that had a theme of “Kill the Indian, save the person.” The healing movement continues as AI/AN people are thriving and moving beyond surviving. In the words that I use to inspire others, “Cry, heal, forgive, and let your tears be the food that waters your future happiness….”

Some countries in the world have made formal apologies to their Indigenous peoples as a result of colonization, and this has made it easier for the indigenous population to move on. As stated in the Australian Parliament: “For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants for their families left behind, we say sorry. To the mothers and fathers, the brothers and sisters, for the breaking up of families and communities, we say sorry. And for the indignity and degradation thus inflicted on a proud people and a proud culture, we say sorry. We the Parliament of Australia respectfully request that this apology be received in the spirit in which it is offered as part of the healing of the nation” (Apology to Australia’s Indigenous People. 2008).

Yes, a formal, sincere apology would be helpful. We are not saying that an apology is the answer to all the devastations that have occurred, but it’s a beginning for awareness, understanding, and maybe trust. To the question: “Why don’t they get over it and move on?” I would reply, “Come live in our world for a while…. Come join our trainings, and I guarantee that your question will be answered.”

References

Barnes, P., Adams, P., & Powell-Griner, E. (2010). Health characteristics of the American Indian or Alaska Native adult population: United States, 2004–2008. National Health Statistic Reports, 20, 1–22.

Bauer, U. E., & Plescia, M. (2014). Addressing disparities in the health of AI/AN people: The importance of improved public health data. American Journal of Public Health. Published online ahead of print April 22, 2014: e1–e3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301602

Blauner, R. (1972). Racial oppression in America. New York: Harper and Row. Retrieved from: http://www.freedomarchives.org/Documents/Finder/Black%20Liberation%20Disk/Black%20Power!/SugahData/Books/Blauner.S.pdf

Centers for Disease Control [CDC]. (22 April 2014). American Indian and Alaska Native death rates nearly 50 percent greater than those of non-Hispanic whites. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2014/p0422-natamerican-deathrate.html

Men’s Health Network. (May 2013). A vision for wellness and health equity for American Indian and Alaska Native boys and men. Retrieved from: www.menshealthnetwork.org/library/AIANMaleHealthDisparites.pdf

Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services. (13 February, 2008). Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples. Retrieved from: http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/our-country/our-people/apology-to-australias-indigenous-peoples

Small, C. (1996). The healing of American Indian/Alaska Native men at mid-life. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington).

About the Author

Clayton Small, PhD, has been an elementary, middle, and high school principal on reservations and in urban communities. He has been a faculty member at the University of New Mexico, University of Montana, and Gonzaga University and has served as a CEO for Indian Health Services and directed several nonprofit organizations. His organization, Native PRIDE, provides prevention, wellness, healing, and leadership training throughout Indian Country. He has developed prevention programs for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Indian Health Services, SAMHSA, and the Department of Justice. He has comprehensive knowledge and experience in community mobilization, strategic visioning, Indian education, organizational development, youth leadership, prevention, wellness/healing, team trust building, cultural competency, and creating positive change. Dr. Small conducts training and facilitation nationally and internationally. His programs offer leadership and hope for American Indian, Alaska Native, and First Nations people. Contact: claytonsmall@aol.com

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2014 SAMHSA Prevention&Recovery newsletter and has been reprinted with permission from the author.

Eve’s Fund has supported Dr. Small’s Native H.O.P.E. suicide prevention program on the Navajo Nation for the past seven years and is honored to be part of this important hope and wellness initiative. Click here to read more about this program.